I don’t like The Wasteland. I’ve read it many times now, as it is practically ubiquitous on the syllabus of every university’s undergraduate English Studies programme, and I can see its potential as a poem. Some passages, especially the ones that are meant to echo Dante’s Divine Comedy, are truly beautiful. Yet, I dislike it. I dislike how impenetrable it is, how much Ezra Pound altered Eliot’s initial version, how utterly bleak it is. It reads precisely like what it is: a poem written by a brilliant young man who wants to prove that he’s clever, and achieves that at the expense of creating something that can speak to readers. Literary critics love The Wasteland, and academics teach it all the time. Unfortunately, as was my own experience, this is the only exposure most of us normal people have to Eliot; and most of us give up on Eliot, because we assume he’s simply unreadable.

So, for many years my Eliot books sat untouched on my bookshelf. That was until 2020, when I had the fortune to be able to attend a recital of Eliot’s Four Quartets by the wonderful British actor Jeremy Irons (whom you may know as Charles Ryder from the beloved 80s adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited). That evening is still one of my favourite memories of the early months of dating my husband. I was sceptical that I would enjoy the reading, but I went in with an open mind. I purchased a Faber&Faber copy of Four Quartets - which I still treasure now - at the theatre door, and started perusing it. Little of it made sense. Jeremy Irons has a fantastic reading voice, I knew, but I wasn’t prepared for how much his reading would bring the poems to life. The four poem that make up Four Quartets are not, strictly speaking, narrative poems. I would say that they trace Eliot’s conversion to Anglo-Catholicism, and in that sense they do contain an overarching narrative, but there’s no clear sequence of events. And yet, as Irons was reading the poems, and as I was following along with my copy, I started to grasp some of what Eliot was attempting to communicate. It was like hearing a story of someone who felt lost, someone who thought beauty and goodness and truth were all illusions, but who ultimately goes on a spiritual pilgrimage, and finds faith and meaning at the end of it.

Of course, I later discovered, this is basically what Four Quartets is about. I have since, in the last three years, read a ridiculous amount of literary criticism on Eliot, so I could sit here and tell you of the various critical interpretations of these poems. But that wouldn’t get you any closer to appreciating Eliot as a poet. I grasped the kernel of Four Quartets that evening when I first heard them, and have come to love them more and more upon each re-read (of which there have been many!). These are poems that grow on you as you revisit them; you feel as though you understand the poet behind them better and better each time. Although I would not consider myself an Eliot scholar (I’ve read none of his plays and not all his poetry), the young, arrogant man who wrote The Wasteland is nowhere to be seen in Four Quartets. They are later career poems, and you can read that in every line. They are ‘easier’ to read, less obscure in their allusions, and downright more enjoyable. They also have less technical flair than The Wasteland, and, dare I say it, more substance, more conviction.

It’s hard to know what to quote from Four Quartets to convince you to read them, as all four poems are impossibly beautiful. But since I’ve mentioned that Eliot becomes a more mature, less arrogant poet in my opinion by the time he writes them, I’ll focus on a section that deals with themes of prayer, writing, and faith. The last poem is called ‘Little Gidding’, and takes its name from a wonderfully charming village in Cambridgeshire, England (which I was fortunate to visit this summer!), where in the 17th century an extremely devout religious community formed, headed by Nicholas Ferrar, a scholar and friend of Anglican poet and priest George Herbert. In ‘Little Gidding’, Eliot recounts a past experience of visiting this village and its little chapel, where Nicholas Ferrar and his family would pray several times a day. In one of my favourite passages, Eliot writes:

You are not here to verify,

Instruct yourself, or inform curiosity

Or carry report. You are here to kneel

Where prayer has been valid.

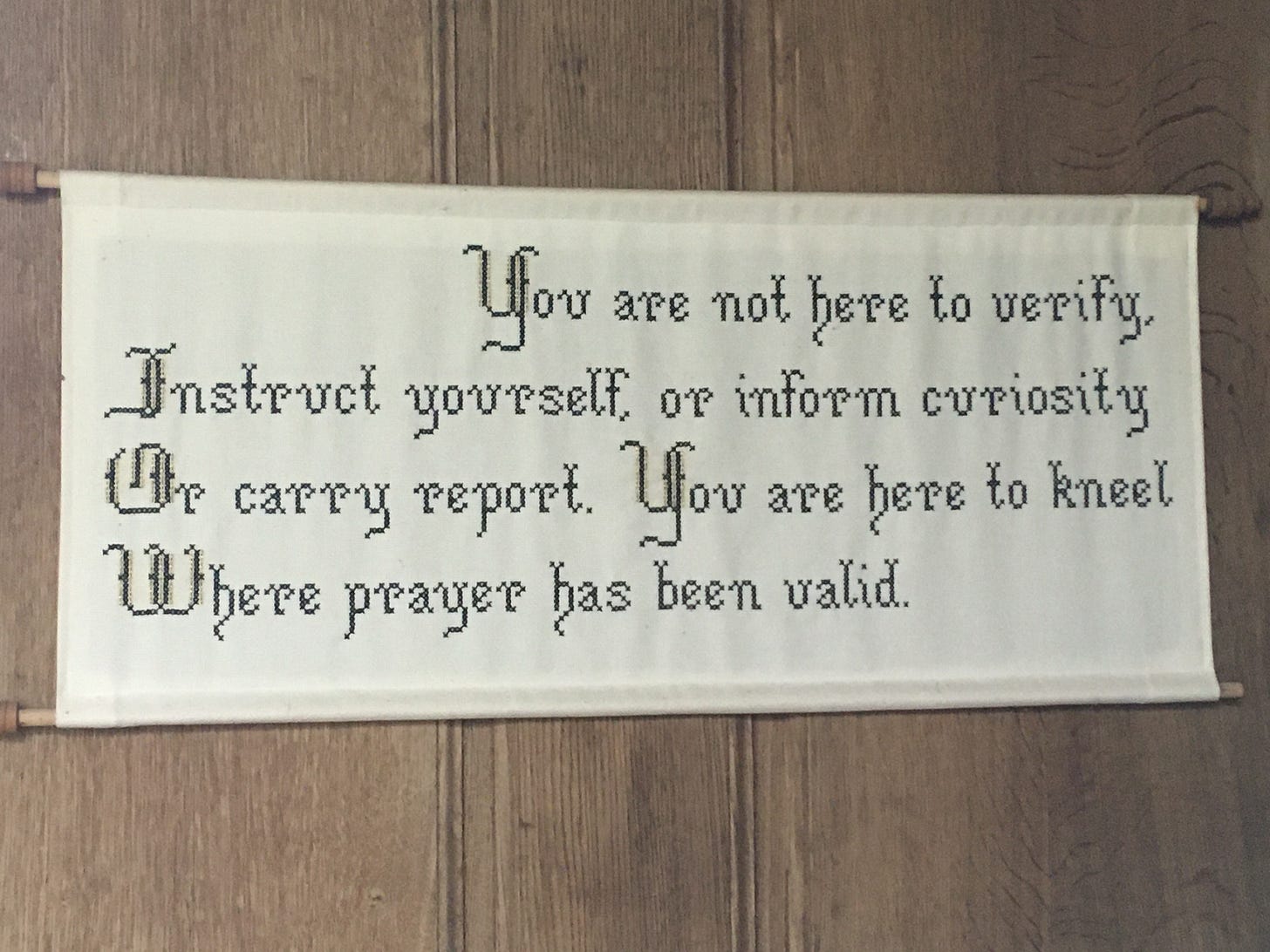

Here is this same passage embroidered and hung up inside the Little Gidding chapel:

I’ve often pondered the meaning of those lines. If you will bear me going all English Studies on you for a moment, all the verbs used ‘verify’, ‘instruct’, ‘inform’, ‘carry report’, make you think of seeking knowledge that can be proven, but doing so for its own sake. This, Eliot writes, is not our purpose. Rather, our purpose is simply to ‘kneel’ and pray. He is speaking to us, but I suspect to himself, also. As a poet, he attempted to be a virtuoso in his youth. But with Four Quartets, he is focusing instead on trying to recount his journey to faith, and he is attempting to do so in humility, kneeling, almost as though his poetry is itself a form of prayer. This has deep personal resonances for me. I am also someone who has a tendency to want to be perceived as ‘clever’; I am often ambitious in the wrong way; I often forget that I should approach writing with an attitude of humility. But every time I reread this passage in ‘Little Gidding’, I am once again called to prayer; I am reminded that I achieve nothing without faith.

I love Four Quartets more and more the more I reread and know them. They seem so personal to me, and yet they are also so universal in the experiences of doubt, disillusion, and desire for God which they portray. If I have at all made you curious to read them, go do so right now. They are poems that grow with you as you grow older, and the earlier you start, the more time you’ll have to grow with them.

Assist the error, and perhaps it will transform into a case.

Caresses the case, and maybe once, you will receive a small gift.