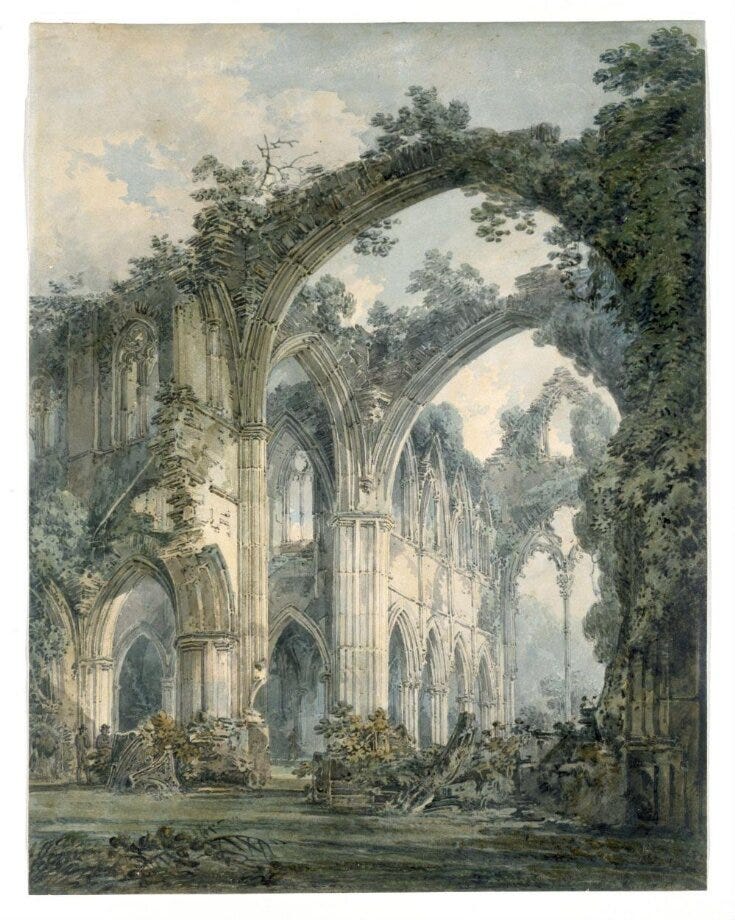

Last weekend was our last before our move into a new home. My in-laws were happy to look after our toddler, and so we took the opportunity to go away for a couple of days before the madness of packing and unpacking furniture begins. We were close enough to Wales from my in-laws’ house, and I had always wanted to visit Tintern Abbey: the choice seemed obvious. I must admit, I was worried I would be disappointed. I had read William Wordsworth’s poem about Tintern Abbey many times over the years; I had seen beautiful paintings of it; I had imagined what it would have been like for people to visit it in the 18th-century, when what we now call ‘tourism’ had just emerged in the Wye Valley. But often, a place met through its artistic depictions fails to live up to expectations. I am happy to report that Tintern Abbey did not, and today I want to tell you a little bit about why I enjoyed it so much.

We first started using the term ‘picturesque’ in its current sense in the 18th- century thanks to William Gilpin, who defined it the term as ‘expressive of that peculiar kind of beauty, which is agreeable in a picture.’ In 1782, Gilpin described the picturesque beauty of Tintern in his Observations on the River Wye and several parts of South Wales (see the British Library's description here). Back then people didn’t have cameras, of course. If you wanted to remember your visit to a particularly beautiful part of the country, you’d have to sketch whatever you saw. Or if you were not pictorially inclined, you could commit the sights to memory - and even write a poem about it years later. The latter is what Wordsworth did in his well-known poem ‘Lines Written a Few Miles Above Abbey, on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye during a Tour, July 13, 1798’. I have loved this poem for a number of years, but never so much as when my husband read it aloud to me in Tintern Abbey a few days ago. I have copied for you here my favourite section from it, where Wordsworth reflects on how he sees nature differently now that he is older, than as a young man.

For I have learned

To look on nature, not as in the hour

Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes

The still sad music of humanity,

Nor harsh nor grating, though of ample power

To chasten and subdue.—And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things. Therefore am I still

A lover of the meadows and the woods

And mountains; and of all that we behold

From this green earth; of all the mighty world

Of eye, and ear,—both what they half create,

And what perceive; well pleased to recognise

In nature and the language of the sense

The anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse,

The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul

Of all my moral being.

Memory, for Wordsworth, is a meaning-making faculty, and the seat of his ‘moral being’. He recognises how much his view of nature has matured since first visiting Tintern several years prior, as a radical and reckless twenty-three year old, but this does not exactly bring him pain. Rather, it brings a melancholic sort of joy: he sees human life teleologically, and thus believes that remembering past experience is essential in shaping his understanding of his current self. Nature, at once always changing, and yet much more long-lived compared to the span of our lives, is for Wordsworth a sign of permanence, an ‘anchor’. The abbey at Tintern, on the other hand, is in ruins. But even that has its own beauty, because it is a reminder of the past, of our very desire to remember.

I’ve always been struck by how similar Wordsworth’s view of memory in ‘Tintern Abbey’ is to the character of Fanny Price’s own musings on memory in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. Here is what Fanny says in chapter 22 of the novel:

‘If any one faculty of our nature may be called more wonderful than the rest, I do think it is memory. There seems something more speakingly incomprehensible in the powers, the failures, the inequalities of memory, than in any other of our intelligences. The memory is sometimes so retentive, so serviceable, so obedient; at others, so bewildered and so weak; and at others again, so tyrannic, so beyond control! We are, to be sure, a miracle every way; but our powers of recollecting and of forgetting do seem peculiarly past finding out.’

For Fanny, too, memory makes meaning of the events in our lives, though she is more realistic than Wordsworth about the ways in which our memory can fail us as well as serve us. Memory, Fanny recognises, is a flexible and sometimes unpredictable faculty. We cannot always control what we recollect and when. But it is also ‘wonderful’, as Fanny says, when memory allows us to piece together moments in our lives that may at first appear disconnected. This is what Wordsworth famously calls ‘spots of time’ in Book XII of his Prelude. A ‘spot of time’, for him, is a very powerful memory that, seen together with other such powerful memories, allows us to give shape to the narrative of our lives. These spots of time have a ‘renovating virtue’, Wordsworth goes on to say, precisely because they also allow us to make sense of suffering and loss.

I had all of this in mind when visiting Tintern Abbey. As my husband was reading the poem to me, I started thinking about my own spots of time. The ones from my childhood are a little hazy. There is one memory I have of gazing at the stars one night when I was around six, in a Italian summer of my youth. I was terrified by how big the sky looked, and wondered what my purpose on this earth was. The memories of my early adulthood are more defined. The first that came to mind was a late evening in June of 2019, right before my graduation in Durham. It was a beautiful full moon. I was sitting by the river Wear with a dear friend (shout out to Maggie if you’re reading this), looking at the moonlight shining on the dark, trickling water like liquid silver; we were talking about what would happen after university. I remember feeling so peaceful at the time, yet full of excitement, at once sad to be leaving a place I had grown to love, and longing for new adventures. I also remember thinking that I would recollect this moment spent with a close friend, on what felt like the brink of our proper adulthood, for a long time. I was right.

My second spot of time happened a little over a year later, in August of 2020. My now-husband and I were in the Lake District with my parents during those brief weeks in-between lockdowns. One day we went to visit Grasmere, where Wordsworth himself is buried. Always an intrepid swimmer, and a particular lover of lakes, I decided to swim across Grasmere lake and back. I remember how cool and still the water was. I remember the peacefulness. Most of all, I remember the look of relief on my then-fiancé’s face when he saw me approaching the shore on my way back. I remember being able to tell how much he loved me, and wondering what our life together would be like once we got married.

And now I know. We have lived in three different countries together in two years of married life. We have two children. We have started and finished jobs and degrees. We have had much loss and much joy. So, our visit to Tintern Abbey, on the eve of a new chapter in our lives as we are about to move into a new home, will no doubt become another spot of time for me. I will always remember the feeling of quiet when visiting the abbey, like time had stood still for a while to allow us to slow down. I will remember wishing we could have stayed there for longer. I will remember hoping that we would one day visit Tintern Abbey again with our children, and recollect our past selves, and a past time in our lives, and smile at how much has happened since. I am grateful for all the spots of time that have shaped my memory so far.