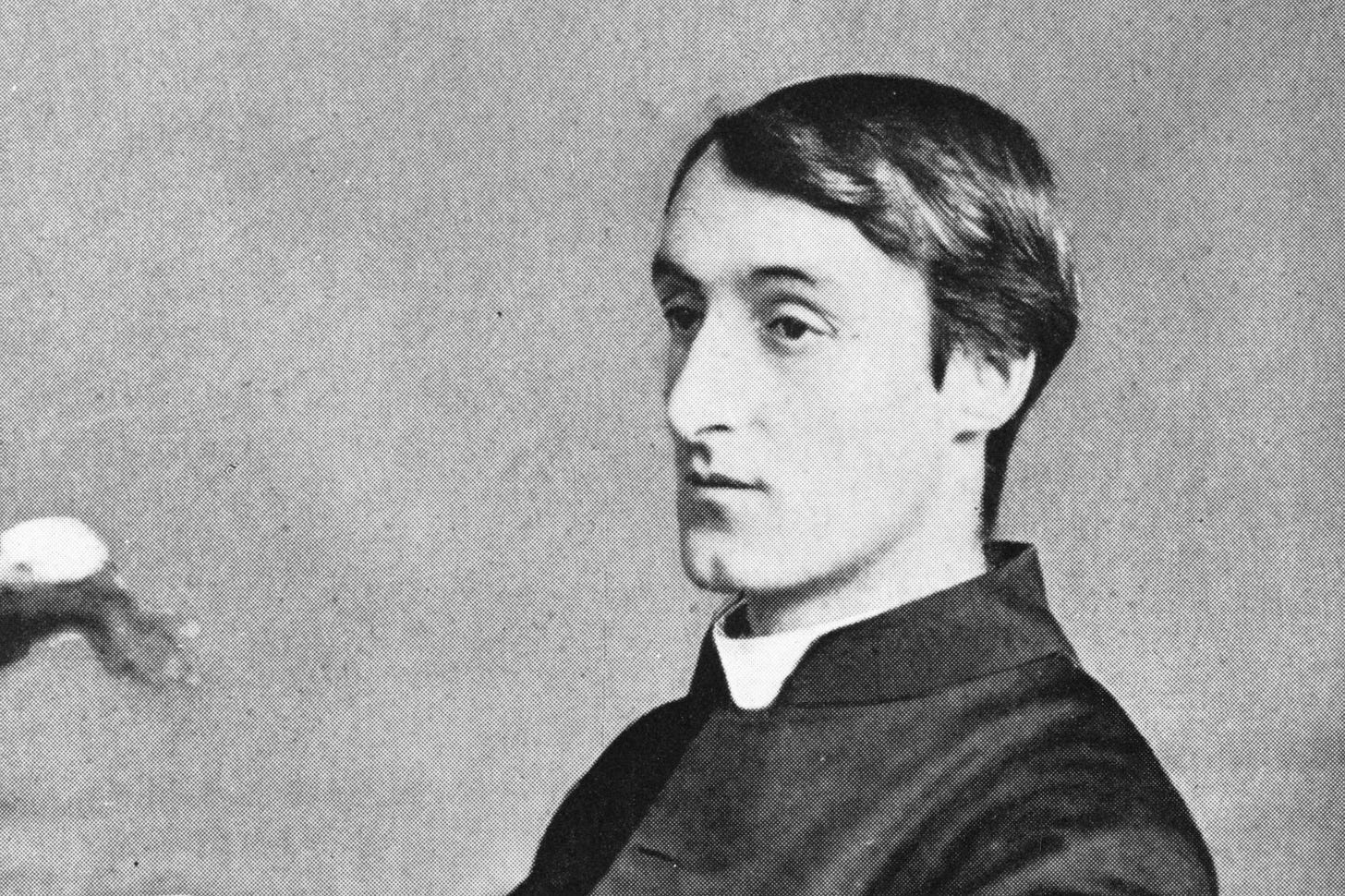

I preface this by saying that I am not even close to being an expert when it comes to the works of English Victorian poet Gerard Manley Hopkins. I approach his poetry as a child would: with a sense of wonder, and loving what I see without fully grasping its meaning on an intellectual level. So today, let this post be less of an argument about why you should read Hopkins, and more of an invitation from a fellow reader.

Now, the autumnal season is normally dominated in the online reading world by John Keats’ famous To Autumn. Mind you, I love that poem, too. But it’s all about the earlier part of autumn, when blackberries and figs and sweetcorn and apples are harvested, just before the coming of the chillier days. It’s really more about late summer than it is about autumn. Much more underrated - but in my opinion, equally delightful - is one of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ lesser known poems, ‘Inversnaid’. Here it is in all its glory:

Inversnaid (1881)

This darksome burn, horseback brown,

His rollrock highroad roaring down,

In coop and in comb the fleece of his foam

Flutes and low to the lake falls home.

A windpuff-bonnet of fáwn-fróth

Turns and twindles over the broth

Of a pool so pitchblack, féll-frówning,

It rounds and rounds Despair to drowning.

Degged with dew, dappled with dew

Are the groins of the braes that the brook treads through,

Wiry heathpacks, flitches of fern,

And the beadbonny ash that sits over the burn.

What would the world be, once bereft

Of wet and of wildness? Let them be left,

O let them be left, wildness and wet;

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.

What I find so appealing and refreshing about this is how the description of Inversnaid (a small village on the bank of Loch Lomond in Scotland) is at once eerie and magical, and yet perfectly down-to-earth. Hopkins is, at a basic level, simply describing the landscape as it is, not as he sees it through the eye of his imagination or through the memory of past feelings (I’m looking at you, Wordsworth!). There are few of the Romantic flourishes and Latinate diction you’d find in Keats’ To Autumn. Perhaps ‘dappled’ is the most Keatsian word that appears in the poem, but otherwise, Keats would never be so bluntly Anglo-Saxon in his diction. And unlike To Autumn, this is the perfect poem to read in late October and especially November, when the remaining warmth of late summer has gone, the light outside gets colder and sharper, and there is a harsher quality to everything we see in nature.

Nonetheless, this is a magical time of the year in its own right. My favourite stanza is by far the last one, where Hopkins celebrates ‘wet’ and ‘wildness’. So many of us prefer warmth and sunshine; I’m almost ashamed to admit this as a native Italian, but I’m much more partial to the rainy, cloudy days of the British Isles. There is comfort in the wild and untamed, in the sight of uncultivated nature. And even as we grieve the loss of flowers and fruits, wet and wildness remind us that the Christmas season is just around the corner. On a more personal note, as I quickly approach my second baby’s due date, I’m going to enjoy watching the leaves turn and the weather get colder as I wait for her arrival. Perhaps I’ll make a cup of tea and have my husband read ‘Inversnaid’ aloud to me. That certainly sounds like a wonderful weekend plan.

The autumn, so similar to the seasons of a human soul, is almost a second spring, when every falling leaf seems like a flower, and the tree that gives it up, does not die, but watches it fall, and patiently waits for it to be reborn, and for a new flower, the coming spring, to be born.